Umberto Eco – A Library of the World

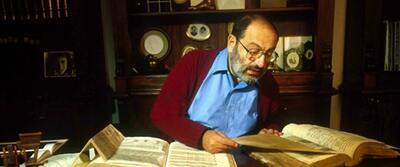

This lively and engaging documentary could just as well be titled “The Labyrinths of Umberto Eco.” The Italian scholar, essayist, novelist, lecturer, and polymath, who died in 2016 at the age of 84, owned not just a prodigious number of books, many of them antiquarian oddities; he absorbed over his lifetime a repository of knowledge that led down many corridors and around corners and snaky paths, allowing him to make astonishing and sometimes disquieting cultural connections. What he did was called semiotics—and the practice is just as crucial to his popular fictions The Name of the Rose and Foucault’s Pendulum as it is in his academic work. Very often, the result of his enthusiastic investigations demonstrated the truth of the Biblical adage about there being no new thing under the sun.

So you think Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire, a “fake” poem followed by an addled “annotation” that adds up to a sardonic yet tragic narrative, is some kind of triumph of modernism? Well, yeah, it is, but in Eco’s collection, there’s an 18th-century book by Thémiseul de Saint-Hyacinthe called The Masterpiece of an Unknown, which is a long mock-commentary on a nonsense verse, written about by Eco in his book La Memoria Vegetal, which I think has yet to be fully translated into English, which is a shame.

The movie, directed by Davide Ferrario, combines archival interview footage of the ever-lively Eco, contemporary scenes of his family and friendly scholars poring over his incredible volumes and their often macabre illustrations, and readings of Eco’s work by actors. These latter moments are sometimes staged in a style that gets a little cute (complete with animation that gets a little cute), but they convey, to some extent, the breadth of Eco’s thought. These components are pillowed by beautiful shots of notable libraries the world over, one so futuristic in design that I doubted it was real, but the end credits confirm it is. There’s not much Eco Origin Story here; he tells a funny story about how as a student, he entered an arrangement with a theater manager to see plays cheap or free if he and his friends applauded rousingly enough, then recalls that he always had to leave before the last act, so he spent many years, for instance, not knowing “what happened to Oedipus.”

While the twists and turns of Eco’s mind, and his delight in what are called “fake books,” have a mind-blowing force to them, Eco himself is not blind to how manufactured knowledge can harm or kill. He calls our own brain the source of “organic memory.” Books, physical books, are vegetal memory. The silicon chips in our phones and computers represent mineral memory. A great memory isn’t always a good thing. Eco cites one of his (and everybody’s, really) favorite writers, Jorge Luis Borges, whose short story Funes, The Memorious is about a man who remembers everything. “And is an idiot,” Eco bluntly states. A good memory is a selective one. Hence, according to Eco, the Internet is “the encyclopedia, according to Funes.”

Later, he muses that it is only in fiction that we encounter irrefutable truths. To this day, some people insist that the world is flat, and yet, Eco wryly notes, nobody questions that Clark Kent is secretly Superman. After the screening of the movie, I found Eco’s pronouncement borne out as I lunched at a well-known West Village pizza joint. Some guy came in with his kids and said loudly, “This is where Spider-Man works,” for indeed, the joint, albeit at a slightly different location, is where Tobey Maguire has a delivery job in the first Sam Raimi Spider-Man picture.

Because this documentary intends to celebrate Eco’s life, work, and books, it doesn’t follow through on the darker currents that the work uncovered. It’s funny when Eco compares himself to The Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown and says, “He and I read the same books; only he believed them.” It’s not so funny when Eco speaks of the anti-Semitic forgery of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. For as much as Eco saw how the written word could elasticize reality, he invariably spoke up for that reality while delighting in some ways that literature could distort and codify it. His theorizing on whether Sir Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s works is a hilarious debunking that some souls might not actually see as a debunking. The best way to explore Eco’s world is via his actual body of work, and this picture made me want to revisit some of his literary labyrinths immediately.

Now playing in theaters.